- Social media zealots preaching intolerance have supercharged Indonesia’s recent dive into Islamic ultraconservatism, squeezing out minority groups

- You can’t even wish Christians a ‘Happy Christmas’ any more, apparently. But Aan Anshori and his Islamic civil society organisation aim to change that

Wishing someone a “Merry Christmas” can be fraught with difficulties in Indonesia these days, as the creep of religious conservatism reaches further into every aspect of life in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation.

“It’s not OK for Muslims to say it,” said Surabaya resident Dini Priyastuti, explaining that in her understanding of Islam the festive greeting was forbidden. “I see some people taking selfies near huge Christmas trees at malls [too]. That’s also wrong.”

Nurul Choirunnisa, a fellow Surabayan, said she no longer offers her friends or neighbours Christmas greetings after hearing sermons against the practice on social media. “I now feel so conflicted so I stay away from non-Muslims at this time of the year,” she said.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

Similar sentiments – echoing the sermons of radical preachers who have weaponised social media to spread their message of religious conservatism and intolerance – can be heard with increasing regularity across Indonesia’s vast archipelago.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

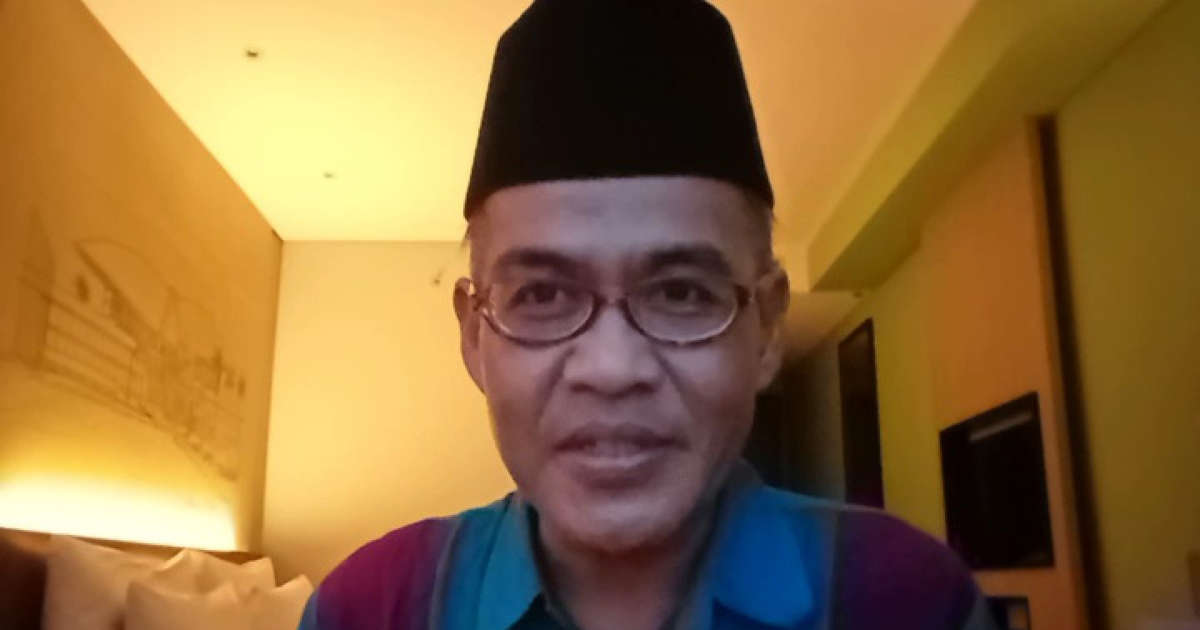

Muslim cleric Aan Anshori speaks into his smartphone camera as he delivers his Christmas goodwill message. Photo: Handout

The result is increasing polarisation – something Aan Anshori, a progressive Muslim cleric from Jombang in East Java, wants to nip in the bud. He’s determined to spread festive cheer and, more importantly, do his bit to neutralise Indonesia’s increasingly spiky public discourse.

“For me, wishing someone of a different faith my best wishes for their celebration is not an act that weakens my faith as a Muslim,” he told This Week in Asia. “In fact, it reinforces my faith and affirms the beauty of Islam.”

Anshori heads the Jombang chapter of Gus Durian, an Islamic civil society organisation advocating for pluralism and tolerance for minority groups.

Each year the organisation produces customised Christmas video messages for delivery to churches and Christian groups across Indonesia and abroad, extolling the things people of all faiths have in common.

‘Religion was forced on me’: surviving Indonesia as an atheist

They might just be simple video messages – but in a time of angst, bluster and heightened religious sensitivity, the message resonates.

“We want to normalise the idea that it is fine for Muslims to send greetings and even celebrate [holy days] with people of other faiths,” Anshori said.

Peace-loving Muslims, he stressed, must never tire of showcasing the tolerant face of Islam.

“The existence of other faiths alongside Islam is a crucial factor in keeping Muslims grounded in the reality of pluralism. Coexisting with them is a great learning curve in humanity,” Anshori said.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

Aan Anshori and members of the Jombang chapter of Gus Durian visit a local church as part of their Christmas itinerary. Photo: Handout

An antidote to polarisation?

Gus Durian’s Christmas greetings are a welcome tonic for many living in a society bedevilled by division, where religious minorities such as Christians can find themselves squeezed out by ultraconservative forces and their harsh brand of identity politics.

“I played Gus Aan’s message at our Sunday service,” said Reverend Anita Malonda, using an honorific for Anshori commonly reserved for clerics on Java. “I could tell everyone in my congregation was touched. This should be made into a tradition for all the faiths in the country in order to foster better understanding and kinship.”

In recent years, Indonesia has seen its status quo rocked by radical clerics with large social media followings sowing discord and dogmatism.

Support for sharia law is also rising – a September poll by Lembaga Survei Indonesia found that 12.5 per cent of its 1,200 respondents supported the introduction of Islamic law, a 3.2 per cent jump from a similar survey in 2017.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

Reverend Anita Malonda said ‘everyone’ in her congregation at Gemindo Church in East Jakarta was ‘touched’ by the Christmas message from Gus Durian. Photo: Handout

A year before that earlier poll was taken, hundreds of thousands of religious hardliners protested in Jakarta against its Christian Governor Basuki Tjahja Purnama – an ethnic Chinese politician better known as Ahok – who was accused of blasphemy against Islam.

Gus Durian’s Christmas message, which Reverend Malonda played to her congregation at Gemindo Church in East Jakarta, simply conveyed that no harm is done when Christians and Muslims interact and socialise, nor does it cause any loss of identity.

For Reverend Leonard Andrew Imanuel, the pastor of GKI Church in Sidoarjo about 50km from Jombang, the video messages are an intuitive way of cutting through divisions.

“I believe by involving young Muslims in this initiative [Anshori] wanted to make sure they had real life shared experiences with people of other faiths, in this case, Christians,” he said. “Coming into contact with ‘the other’ is something Gus Aan champions consistently.”

With Indonesia’s ‘heresy app’, religious harmony hasn’t a prayer

Founded in 2012, the Gus Durian organisation is a national network of adherents working to “preserve the intellectual legacy” of Indonesia’s fourth President Abdurrahman Wahid, better known as Gus Dur. Some 1,300 delegates were at its last annual congress in October in Surabaya.

Wahid, who was only in office from 1999 until his removal two years later, earned renown for his progressive views as a cleric who won the Magsaysay Award – often called Asia’s Nobel Prize – in 1993 for Community Leadership.

He was a reformist, whose grandfather founded Nahdlatul Ulama – now the largest Islamic organisation in Indonesia, and the world.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

Abdurrahman Wahid pictured in 2001 shortly before being he was removed from his post as president by Indonesia’s parliament. Photo: Reuters

During his short time in office, Wahid repealed a ban on Indonesian Chinese practising Chinese culture and enacted other reforms.

But his changes met resistance and in 2001 he was toppled by parliament. His critics, especially among Muslim hardliners, accused Wahid of heresy and harbouring anti-Islamic views for working to foster closer ties with other faiths.

Wahid continued to promote a socially progressive platform and speak out against Islamic ultraconservatism right up until to his death in 2009.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

A woman walks past a Santa Claus balloon installed by a shop in Jakarta to celebrate the Christmas holidays. Photo: AP

‘This is heresy!’

The advent of social media has supercharged the spread of ultraconservatism in Indonesia by providing prolific hard-line Islamic preachers such as Abdul Somad Batubara, Khalid Basamalah and Adi Hidayat with a platform to spew forth their messages of intolerance.

In one public sermon widely shared on social media, Batubara claimed a Muslim who wishes a Christian “Happy Christmas” is endorsing Christianity over their own faith by acknowledging that the birth of Jesus was the “birth of the son of God”.

“This is heresy! In Islam God is neither begotten nor begets,” the 45-year-old cleric said in the 2018 sermon.

Hidayat also decrees in his sermons that sending greetings to non-Muslims on their holy days is forbidden by Islam, but he proposes a compromise.

© Provided by South China Morning Post

People enjoy artificial snow at a Jakarta shopping centre as part of a Christmas-themed event. Photo: Reuters

“If the greeting doesn’t mention Christmas at all, that would be permissible. Just keep it neutral,” he has said.

Practising Roman Catholic and Jakarta resident Albert Gondokusumo said it had been years since his Muslim neighbours wished him ‘Happy Christmas’.

“I’m not surprised with all these preachers telling people not to. There was even a fatwa against it,” the 65-year-old said.

But the lack of conviviality cuts both ways; Gondokusumo says he no longer wishes his Muslim neighbours happy Eid either.

Singapore denies entry to extremist Indonesian preacher

The communal atmosphere may appear bleak, but Anshori believes small gestures can carry outsized messages.

“As [followers of] the majority faith [in Indonesia], Muslims must take the lead in reaching out to the others,” he said.

In his Christmas video to Surabaya’s Immanuel Church, Anshori, smiling and wearing a peci hat as he peered into his smartphone’s camera, reaffirmed his belief in the important role both Islam and Christianity can play in Indonesia’s future.

“I’m confident when our two faiths remain steadfast in efforts to nurture pluralism and universal love – as reflected in the teachings of Christ – peace will follow,” he said.

More Articles from SCMP

Chinese companies back on track in Tanzania after winning US$2.2 billion railway contract

Transport services between Hong Kong and Macau to return, but some question casino hub’s reopening amid rising Covid-19 cases

Chinese ambassador admits Russian invasion of Ukraine has hurt relations with EU

China urged to restore normal working lives to lift consumption, vouchers seen to have limited long-term impact

This article originally appeared on the South China Morning Post (www.scmp.com), the leading news media reporting on China and Asia.

Copyright (c) 2022. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.