It feels like my childhood is being dismantled, not slowly, brick-by-brick, but more with the force of a wrecking ball. A few weeks ago, Roald Dahl, one of the best-known children’s authors of the twentieth century, had a number of his classic books revised. The publisher, Puffin, hired a team of sensitivity readers to pore over his words and make hundreds of changes. Dahl’s often darkly comic and memorable characters seemed to particularly annoy the censors. Anything related to physical appearance has either been removed entirely or had passages added to justify Dahl’s use of descriptive adjectives.

In the fight for free speech, culture warriors have brought a new weapon onto the battlefield. In recent years, sensitivity readers have become the most talked-about people in literature. Essentially freelance copy editors, they are hired by publishers to read new manuscripts and remove all traces of politically incorrect terminology, which now appears to be just about anything. They are to free expression what a guillotine is to a hairdresser. Under their reproachful glare, the written word is under threat.

So it should really not come as a surprise that fiction’s new moral guardian has turned its censorious gaze towards that well known bastion of filth and depravity: fairy tales.

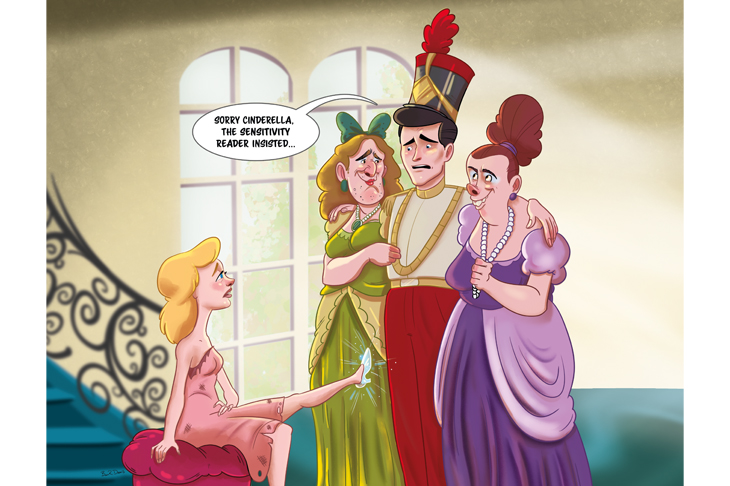

A few days ago, the UK Telegraph reported that Ladybird had brought in sensitivity readers to go over the publisher’s back catalogue and reexamine a number of children’s books from its vintage collection. Classic fairy tales like Cinderella and Snow White, and the characters and plots in the stories, are said to be of particular concern to sensitivity readers. In woke parlance, fairytales are now problematic.

You won’t be surprised which perpetually offended demographic is to blame. When it comes to fairy tales, a recent survey revealed that almost half of those under the age of thirty found them to be inappropriate for children. While a whopping 89 per cent believe they reinforce outdated – what normal people call ‘traditional’ – gender roles.

This incessant need to eradicate offence is something I find deeply disturbing about millennials, and to a certain extent, Generation Z-ers. Emblematic of the purity of their political opinions and the self-righteousness of their convictions, they wish to erase everything from history. Some of these tales date back thousands of years. The reason they have survived relatively unscathed might have something to do with what they can teach us. This is because fairy tales contain a number of universal truths that are as relevant now as they were a millennium ago.

For example, in the tale of the Three Little Pigs, the moral lesson was about the value of hard work, while Goldilocks warns you not to enter someone else’s home without permission. In Little Red Riding Hood, we learn that we should be cautious about trusting strangers, while Beauty and the Beast taught children to look beyond superficial things like physical appearance. Teaching children that there’s more to life than identity? I can see why they want to consign them to the dustbin of history!

Yet the history of telling stories dates back tens of thousands of years. Long before they were recorded on paper.

Since the dawn of time, our ancestors have used tools to paint pictures, express thoughts, and, most importantly, tell stories. In 2017, an important discovery was made on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. A team of archaeologists found what is thought to be the world’s oldest known cave painting. Located in a limestone cave, the image shows eight human-like individuals hunting six animals. The work, which experts date at almost 44,000 years old, is thought to be the earliest known depiction of storytelling through pictures.

These stories were created to outlast the finite nature of our existence. A cultural legacy to be passed down to future generations. Literature, and by extension all art, is an expression not just of who we are but, as with the Indonesian cave painting, of what we were. As a visual medium, literature has the ability to portray a powerful and unique story. Literature can do this because those who write it are free. When unencumbered by the strictures of censorship, an artist’s vision is free to flourish. They are free to be provocative, challenging and controversial. To do this, you’re always going to risk offending someone. I know it’s hard for the progressive generation to accept, but offence is taken, not given. I am sorry, but there’s no right to ‘not be offended’.

Among censorship advocates, a common strategy is to demand that classic works of fiction conform to the higher ethical standards we have set for ourselves today. But you cannot judge past morality by our contemporary ethical and cultural norms. History is both a complex and nuanced affair. As much as it might shock today’s youth, some may have assumed someone’s pronouns.

I don’t entirely blame the kids. The far-Left’s long march through the institutions is complete. Universities have been captured by a highly radical social constructionist vision of human identity. One such discipline, poststructuralism – where a lot of this nonsense comes from – argues that meaning, and hence objective truth, is not fixed but open to constant interpretation. Students have been taught to deconstruct the text and to view language solely in terms of a power relationship between oppressor and oppressed. Through this lens, Prince Charming can no longer wake Snow White with a true love’s kiss, as this perpetuates rape culture; instead, he must now obtain her permission.

Fairy tales are more than just stories. Not only do they teach children important moral lessons, but they have the ability to resonate with all of us. They reveal timeless, universal truths about the human condition. Stories show us the strength of love and the true meaning of friendship; the dangers of anger, greed, and conflict; and we can learn about the power of kindness or the darkness of cruelty. They can make us laugh and make us cry. Above all, they show us what it means to be human.

If sensitivity readers have their way, it won’t stay like this. The changes being made in the world of literature are insidious, but their impact is both immediate and profound. Political pandering is slowly draining all the fun and individuality out of everything we consume in a relentless crusade to avoid offending people.

The creativity and imagination that turn a simple idea into reality are gifts we must treasure. Yet the next generation treats free expression with utter contempt. The end result is a cold, sterile world – one ruled by fear and shame instead of passion and curiosity.

It’s not all bad news. Swift Press is a new company that specialises in publishing cancelled authors and books that other publishers will not publish. When Kate Clanchy had her Orwell Prize-winning memoir Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me pulled apart by sensitivity readers, she parted company with her original publisher and had the book reissued by Swift Press. The independent publisher is only two years old, yet they have already sold close to a quarter of a million books.

Now there’s a fairytale ending.