© Provided by National Post

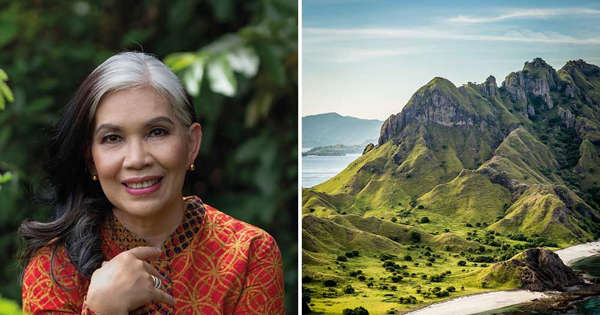

U.K.-based chef Petty Pandean-Elliott is the author of three Indonesian cookbooks. PHOTOS COURTESY OF PETTY PANDEAN-ELLIOTT/GETTY IMAGES

Our cookbook of the week is The Indonesian Table by Petty Pandean-Elliott. To try a recipe from the book, check out: crudité, tempeh and tofu with shrimp paste sambal; pork satay with chili, ginger and lime; and sour fish soup.

Home to nutmeg and cloves, the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia forever changed the world’s cuisines. Spice blends such as Chinese five-spice powder, French quatre épices, Indian garam masala, and Moroccan ras el hanout simply wouldn’t be the same without them.

“Sadly, I think the world forgot how big the influence from the Spice Islands was,” says Petty Pandean-Elliott , an Indonesian-born, U.K.-based chef and author.

An astounding 30,000 species — more than half of all the spice in the world — originated in Indonesia. Starting in the 15th century, the archipelago played a pivotal role in the spice trade, shaping food traditions far and wide.

“It’s extraordinary, isn’t it? Because it happened many, many centuries ago, and still, can you imagine Christmas without nutmeg and cloves? Plus ginger, perhaps,” adds Pandean-Elliott with a laugh.

In her third book, The Indonesian Table ( Phaidon , 2023), Pandean-Elliott explores this history of cultural exchange and how it shaped her homeland’s regional cuisine. Just as Indonesian spices flavour the world’s food, Chinese, Arabic, Indian and European cuisines have left a lasting mark on meals in the archipelagic nation.

© Phaidon

Chef Petty Pandean-Elliott shares 150 recipes from her native Indonesia in her third cookbook, The Indonesian Table.

Pandean-Elliott was born in Manado, North Sulawesi, and dedicated one of her previous books, Papaya Flower, to Manadonese cuisine. Manado lies inside the coral triangle, part of the Pacific Ocean that holds more coral species than anywhere else on the planet (not to mention six of the world’s seven species of sea turtle ). Known for scuba diving and snorkelling, it is also a hub of trade in spices (vanilla, cloves, nutmeg), coconut products and seafood.

Manadonese cuisine has had a great influence on Pandean-Elliott’s approach to food, and it’s here that she starts The Indonesian Table. Beginning with Sulawesi, she focuses on the traditions of the country’s eight main regions — including Java, Bali and Sumatra — through 150 recipes.

While nasi goreng, rendang and satay may be well-known outside Indonesia, the same cannot be said for many of the foods Pandean-Elliott grew up with, such as candied nutmeg (manisan pala) and grilled fish with dabu-dabu, a condiment made with calamansi, chilies, mint, shallots and tomatoes.

Dutch colonial rule ended in 1941, but historic influences remain in Manado. This was especially true for Pandean-Elliott’s family. With a half-Dutch paternal grandmother, meals included brenebon , a soup of kidney beans and pork, klapertart , a rum-and-vanilla-scented coconut cake, and kastengel , or cheese sticks. On the other side of her family, Pandean-Elliott’s maternal grandmother, Oma, taught her how to butcher chicken and gut fish, to taste and smell, and combine spice pastes ( bumbu ) with dry spice blends (rempah) and fresh herbs.

Pandean-Elliott moved to Jakarta with her family at age 13, more than four decades ago, “yet I still think of Manado as my home.” Indonesia’s capital held new flavours, with pushcart vendors, hawker markets and family-owned warungs offering dishes she hadn’t tasted before. Growing up there gave her a new appreciation of the country’s cultural diversity, which was important for her to showcase in The Indonesian Table.

“We have 17,000 islands, over 700 dialects, 1,300 ethnicities. So, it’s massive. It’s as if we talked about Europe (as) one country. Can you imagine that? The sheer diversity is just mind-blowing, even for me as an Indonesian.”

Pandean-Elliott points to Indonesia’s official motto: Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity). “If we can value diversity and give respect to one another, I think the world (would) be more beautiful,” she adds. “If Indonesia can keep that forever, it (would be) quite nice to give an example to the world.”

English-language publishers have put out few Indonesian cookbooks; even fewer still written by Indonesian authors. Cooking teacher and food writer Sri Owen , chef William W. Wongso , and Lara Lee , an Australian chef and food writer of Chinese-Indonesian heritage, are a few notable exceptions. But Pandean-Elliott feels that momentum is building due, in large part, to tourism.

In the last seven years, the Indonesian government has expanded its tourism efforts, she says. And not just in hot spots Bali and Java, but many parts of Indonesia . “It’s connected. With tourism and more people going there, then they taste the local cuisine, and there’s more interest. So, I’m very excited with my book. Hopefully, it will contribute to the awareness of regional Indonesian cuisine.”

Although Pandean-Elliott had a strong foundation in food, thanks to the time she spent in Oma’s kitchen and garden, it wasn’t until she and her British husband relocated their young family to the U.K. in 1999 that she found her true calling. They stayed for just two years before returning to Indonesia, but the move changed the course of Pandean-Elliott’s career — from working at an international advertising agency to becoming an award-winning chef.

“My experience living in the U.K. at that time inspired me to explore the culinary world, because I didn’t see any Indonesian food culture around. But it’s so fascinating, (24) years later, it’s still the same. Can you imagine that?” says Pandean-Elliott. “We have several restaurants, two or three. But within (more than) 20 years, there’s no big change.”

Motivated to share a taste of her homeland with her friends and neighbours, Pandean-Elliott immersed herself in cooking. She reconstructed Oma’s dishes with the help of her mother, aunties and cousins. During travels to Bali, Java, Lombok and Sumatra, she researched regional Indonesian cuisine.

“When you live abroad, you’re longing for the taste and the flavour of your home country. Because I’m a self-taught chef as well, I was experimenting cooking Indonesian food with U.K. ingredients at that time. The spices and the herbs were limited in ’99. But now, of course, they’re more available than before.”

Pandean-Elliott started to take cooking seriously and sent in an application for the British TV series MasterChef. Though she didn’t make it to the finals, competing on the show in 2000 was a turning point. “That experience really changed my life,” she says, laughing. “It was so inspirational.”

When she and her family moved back to Jakarta a couple of months later, she returned to advertising. But after another two years, she decided to take the leap and pursue a culinary career.

Today, appreciation for local cuisine is strong in Indonesia, says Pandean-Elliott. But when she returned to Jakarta in the early 2000s, the focus was on European food. A lot has changed, especially in the past decade, she adds, and interest in regional Indonesian cuisine is blossoming.

Though she moved back to the U.K. in 2018, she still visits Indonesia often for work and stays connected to the fast-paced Jakarta food scene.

“It’s just amazing to see the development of how we are celebrating Indonesian food (more than) ever. Now, a lot of young chefs want to explore Indonesian food, Indonesian ingredients. Trying to go back to our roots more. But I suppose around the world there’s a movement … of trying to get to know the food during your grandma’s era or your parents’ era.”

Digging into regional cuisine has been “an amazing journey,” adds Pandean-Elliott. She began writing about food in 2004, and ever since, has travelled throughout Indonesia, collaborating with local and international chefs, visiting traditional markets in remote places and spending time with cooks in Indigenous communities. She drew on memories — some distant, others recent — for The Indonesian Table.

“It’s just a very nice way to promote your own food culture and, at the same time, you learn about other food cultures. And I think through food, we are all connected. Through spices, we are all connected. So, I’m very blessed.”