PROLOGUE

2019

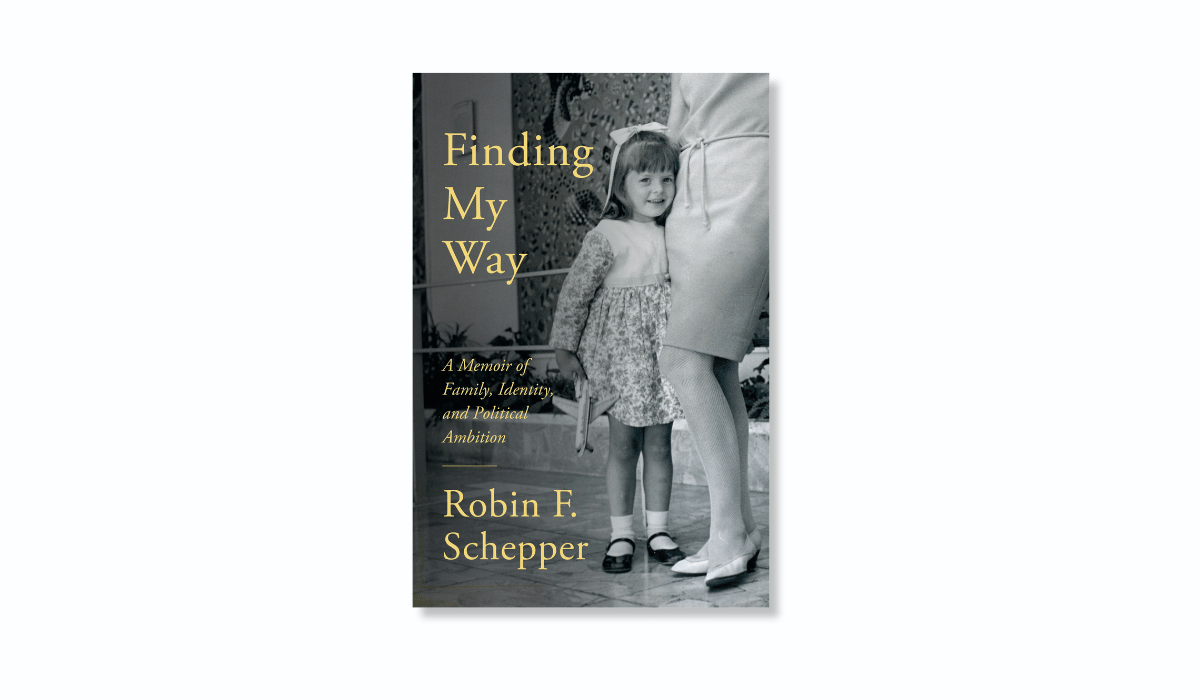

Whenever I open one of the fabric-covered photo albums my mom saved, I find myself tracing the scalloped edges of each picture, captioned with the narrow cursive of my mom’s writing. 1957—Hoffman’s Farm, 1960—Queen Mary. Though I’ve looked through this album, and the others she kept, countless times, I am continually hoping that somehow the pictures will reveal something new. Perhaps today they will unlock the many secrets of my past and give me the answers I crave.

Of course, I now have my own photo albums, ones featuring the life I’ve created around me: my husband, Eric, and the lights of my life, my adopted sons, Shokhan and Marat. These albums also depict my earlier years as well as highlights from my career: the international advance work I did for President Clinton (coordinating with foreign governments, US embassies, and the Secret Service to produce events and every detail of the president’s travels), the four years I spent working for the Athens Olympic Games in Greece, and my first day on the job working for First Lady Michelle Obama, me striding confidently across the White House lawn.

They also reveal one thing for certain: I’ve come a long way.

But there are some truths they will never erase, unlock, or divulge. I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in New York, and according to the Catholic Church, I was a bastard child because my mom never married my biological father. In fact, I never met him or even knew his identity until very recently. On top of that, my grandmother ran a “massage business” out of an upscale apartment building on Seventy-Ninth Street, where she often asked me to help with mundane tasks, like erasing all the messages on her answering machine.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

I grew up surrounded by other family secrets, too, and over the years, the shame of the truth, and the work of keeping all these secrets hidden from the outer world, eroded my sense of self-worth, like a cancer eating away at healthy tissue. Living with secrets also meant living in a family that never behaved how I thought a family should. I periodically demanded the truth from both my mom and grandmother, but they ducked or avoided or placated or outright lied. Eventually, I realized I had no choice about the life I would need to build for myself. I would create my own worth and show everyone that a bastard child could succeed. I would seek out the truth and, in so doing, I would shape my own identity. And most importantly, I would create a family where honesty and love would bind us together instead of DNA.

LIKE MOTHER, LIKE DAUGHTER

1976

When I was thirteen, I wanted to find out more about my grandmother, my mom, and my origins—including more about my father. One afternoon, my mom and I were sitting on her bed looking through her old Pan Am scrapbook. I asked her to tell me stories about her time there.

“Oh, Schatzi, I have told you the stories before. You want to hear them again?”

“Yes, yes, please.” I tried to sit quietly, and I put my hands underneath my butt to contain my excitement.

In the first photo, my very young-looking mom was wearing an elegant dress and was seated at a table with a young man and another couple.

“The first airline I worked for was Capital Airlines, and I was based in DC and Chicago.” Part of her training, she said, was learning how to entertain at dinners whenever she had twenty-four- and forty-eight hour layovers so she could represent the airline well. I thought about how exciting that must have been. Twirling her hair as she talked, she went on to say how much she loved the airlines and all the important people she had met, like Adlai Stevenson when he was running against President Eisenhower in 1956.

“Then one day, I heard Pan Am was looking for stewardesses, especially ones with language skills. You had to be twenty-one, which I had turned in 1956. I knew German, and because of the two years I had at the finishing school in Lausanne, I spoke French too. Plus, they liked my looks. So I got hired.”

“Finding My Way”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

We had been eating pasta while looking through her photo albums, and now she smiled as she looked down at her fork. It was one she had saved from the first-class cabin at Pan Am all those years ago. She didn’t realize I had set that fork out intentionally.

Mom continued. “Those were great days. We wore beautiful silk uniforms, and I worked in the first-class cabin where we used linens, silver cutlery, and porcelain dishes on our transatlantic and transpacific flights. I know I don’t cook now, but back then I would make roasts in the oven on the plane. We also had a film projector on board for movies. It was very elegant. People dressed up to get on the plane, and almost all the passengers in first class were men on business trips.” She grinned. “Let’s just say I got a lot of attention back then.”

I imagined Mom sashaying up and down the aisle and then recalled how she had once been upset that I walked too much like a boy. She had placed a book on my head and told me to walk back and forth in the hallway by putting one foot in front of the other. I thought it was stupid; my feet went in parallel lines, not along an invisible tightrope. But she told me your hips swayed more if you put one foot in front of the other.

I flipped to another picture. “Mom, what about this one?” She was in a bathing suit and high heels, standing next to a ship’s wheel.

“Pan Am encouraged us to take part in beauty contests when we were on our forty-eight-hour layovers.” Again, I imagined my mom walking across the stage while exaggerating her hips. “The layovers were so that we had the opportunity to rest between flights. When we weren’t entertaining, we Pan Am girls would enter beauty pageants with the local girls. In this one, we were in Italy.” Mom pointed to the ship’s wheel in the photo. Its insignia read Italia. “We were initially twenty girls, and then it came down to three. I won third place. The blondes always won first place.”

Mom kept turning the pages. In another photo, she wore a pearl choker, a black 1950s-style dress, and a sheer black shawl over her shoulders.

Mom exhaled deeply. “This was the time of my life. Dr. Sukarno was the Indonesian president, and he chartered a Pan Am airliner in 1958 for a forty-one-day trip to what were called ‘the capitals of uncommitted countries’—otherwise known as neutral countries. Don’t ask me what that means because I can’t remember. I never was a good history student.”

I figured it likely had something to do with the Cold War and meant the countries they visited weren’t part of NATO or the Soviet alliance.

“We deadheaded the plane from New York to Calcutta and met Dr. Sukarno there with his traveling party. He was wearing his traditional hat and sunglasses like in all the pictures I had seen of him from the papers.”

I had seen those pictures too, and what I remembered about him was that he was a dictator. Then I tried to imagine my mom actually liking him. Ugh, how could she?

“His traveling party was all men, and Dr. Sukarno took an instant liking to me. Our first stop was a visit with Prime Minister Pandit Nehru in New Delhi.” She described how crowded the streets of India were and all the beggars that she saw. She was too afraid to get out of the limousine. I, on the other hand, would have gladly gotten out and interviewed everyone around me, trying to find out more about their lives.

Mom sighed as she remembered more details from that trip, like tasting curry for the first time and feeling as though her mouth were on fire. They visited the Taj Mahal, and they went on to Sri Lanka, only a decade earlier known as Ceylon, for twenty-four hours and drank a lot of tea. When she noted that there wasn’t any alcohol on the trip because Dr. Sukarno was Muslim, I wondered if he knew she drank alcohol back home or if she kept it secret from him in the same way I was currently keeping it secret from her that I was in charge of buying beer for my friends because I looked the oldest.

She reminisced about the time their plane was flying over the Red Sea and the crew heard a loud, screaming whine.

“We looked out the windows, and what did we see? Russian MiGs on either side of our plane! It still gives me chills. You know what the Russians did to Grandpa’s family in Austria.”

Luckily, the Russians were just escorting her plane to Cairo, where she then met General Gamal Nasser.

“I felt like I was a president’s wife or a movie star.”

She had a wistful look in her eyes as she talked about Luxor, a barge down the Nile, Damascus, West Pakistan, Burma, and Angkor Wat in Cambodia. It seemed as though she wished she were back there being a stewardess instead of having a pasta dinner with me.

At one point, Dr. Sukarno bought her a purple gemstone ring in Alexandria.

“He was always trying to get more personal with me. I had to walk the fine line of being a welcoming ambassador for Pan Am without getting caught in a compromising position. His chief of staff delivered numerous notes to me from the president, but I said to reply that I was unable to meet him. I was not about to get involved with a head of state. What was the future in that? And of course, he was later killed in a coup.”

I thought about all that. If Dr. Sukarno had been successful in his advances toward my mom, she might have become one of his wives—and I would have never existed.

Later, as we were washing dishes and cleaning up the kitchen, she reemphasized how impressed she had been to meet all those heads of state but also how hard it had been to believe they could be such ruthless leaders. “You can’t imagine how personable and charming they were to me,” she said.

“Mom, people liked Nixon too, until Watergate.”

After a pause, she said I must go and see some of these sights when I got older. “In fact, you need to travel the world and get it out of your system before you’re married and have kids.”

“Mom, that’s why I’m going to be an international photojournalist. So I can travel the world and take photos.”

That night, while doing homework, I considered how a scholarship to a private school could be my ticket to any kind of life outside our little apartment, and I made a vow to myself. I would travel like my mom had when I grew up. Neither of us could possibly have imagined at that time, however, all the people I would meet, and the places I’d visit, when I finally grew up.

Many of my jobs would ultimately take me far and wide, and like my mom, I would also meet heads of state. But it’s hard to imagine anything better than having an office in the East Wing working for the First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama. I had spent the previous four years wearing leggings, T-shirts, fleece jackets, and sneakers in my work as a life coach, and suddenly I had been recruited to lead the First Lady’s Let’s Move! campaign to combat childhood obesity. Some things never change, and in the same way that my mom had to dress in a certain way for her role as a Pan Am stewardess, I dressed for success on my first day in a purple Eileen Fisher dress with a matching jacket, control-top pantyhose, uncomfortable beige high-heeled pumps, and a long necklace that I quickly learned could easily become entangled with the White House ID tag hanging around my neck.

I sometimes think about my mom, and all the luxurious places she visited, when I reminisce about my time at the White House. After my first weekly staff meeting with the First Lady of the United States, I found myself walking downstairs past the Family Theater and making my way through the East Colonnade. Glancing at the pictures lining the walls of all the previous presidents, I wanted to pinch myself. Is this real? The sound of my heels clicking on the marble floor and the murmur of voices confirmed that it indeed was. When I encountered a tour guide leading a group of visitors through the public sector of the White House, I thought about how cool it would be for them to get a glimpse of Marine One on the lawn. Maybe I will too.

The East Wing, the West Wing, and the Residence were not built at the same time, but many rooms connect the different buildings. My daily route took me past the East Garden Room and the busts of historical figures, the White House Library decorated in dark-red tones, and the Vermeil Room with its huge painting of Jackie Kennedy Onassis in a long, flowing dress. I gazed at her portrait on my first day and every day thereafter as I made my way through the White House. Imagine that: I was walking in the same rooms, and taking the same footsteps, as presidents, First Ladies, and foreign dignitaries had. How does a child of a single mom, whose first language wasn’t English, end up walking past this portrait of a woman who embodied American high class and nobility every day on her way to work? Surely, it had something to do with the same good fortune my mom had when she visited all those dignitaries years ago.

From “Finding My Way: A Memoir of Family, Identity, and Political Ambition” by Robin F. Schepper, Copyright © 2023 by Robin F. Schepper. Reprinted in arrangement with Girl Friday Books, Seattle, WA.

Robin F. Schepper served at the highest levels of American politics and government for more than 30 years. She worked on four presidential campaigns and in the Clinton White House, was staff director for the Senate Democratic Technology and Communications Committee under Sen. Tom Daschle, and served in the Obama White House as the first executive director of Michelle Obama’s anti-obesity initiative, Let’s Move! She’s advised numerous nonprofits and helped draft policy reports for the Bipartisan Policy Center. She lives in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, with her husband and two sons.