Indonesians’ present-day notions of beauty are embedded in a long and complex relationship between skin colour and race

L. Ayu Saraswati

Go to any mall in Indonesia and you will find images of light-skinned, if not Caucasian, women modelling the latest fashion, handbags and beauty products. If you have grown up in Indonesia, you are probably familiar with jokes and/or insults thrown at people with dark skin colour which mock the darkness of their skin. No wonder skin lightening products became one of the most popular commodities, touted as ‘crisis-proof’, in Indonesia. But is racial and skin colour hierarchy in Indonesia the same as in other countries, such as in the United States, where lighter is considered better? Do Indonesian women use skin lightening cream because they want their skin to be white like Caucasian women?

The short answer for both questions is no. The longer answer involves a concept that I call ‘cosmopolitan whiteness’.

Notions of beauty

In a study that I conducted using archival research; advertisements, newspapers and women’s magazine analyses; and Indonesian women’s testimonies, I found that: one, preference for light-skinned women predates European colonialism; and that two, although there had been preference for light-skinned women, lighter skin is not always considered better, if the woman’s race is not the preferred race. This suggests complex and intriguing understandings and relationships between race and skin colour in Indonesia.

Prior to Dutch colonialism, old Javanese kakawin (long narrative) poems, adapted from their Indian origins, such as Ramayana, described beautiful women as having white, shining faces, like the full moon. During that time, however, the preference for light skin colour was not yet conflated with race. It was only after Dutch colonialism fully matured in colonial Indonesia (then called the Indies), particularly during the early twentieth century, that preference for light skin colour became decoded as Caucasian white. During this time, images of Caucasian white beauty represented the epitome of beauty in the beauty advertisements published in Dutch women’s magazines.

When the Empire of Japan took over as the new colonial power in Indonesia from 1942 to 1945, they propagated a new Asian beauty ideal: white was still the preferred colour but not the preferred race. Japanese white beauty that became the new beauty standard.

Then, in post-colonial Indonesia and particularly during the reign of Suharto, Indonesia’s pro-American president (1967 to 1998), American popular culture became one of the strongest influences against which the Indonesian white beauty ideal is articulated and negotiated.

The Indonesian white beauty ideal slowly evolved from the preferred light skinned category, called kuning langsat (yellow like the langsat fruit), to putih (white). Here, however, the word putih should not simply be understood as Caucasian white. Interviews with Indonesian women reveal that they do not like bule (Caucasian) white skin since it appears reddish white, like shrimp. They also do not like Chinese white – but do not mind Japanese white. Thus, in Indonesia, the quality of white skin is signified by nationality, race and ethnicity.

The whiteness of a particular skin colour often becomes undesirable because of the race, nation or ethnicity that signifies it. This is most evident in the case of the Chinese. The long history of discrimination against Chinese people in Indonesia seems to surface when these women discuss the ideal skin colour: Chinese skin colour is not preferred. Dutch colonial policies indeed produced a distinct ethnic Chinese capitalist class which contributed significantly to their current status as outsiders in Indonesia. On the contrary, Japanese colonisation successfully instilled the notion of Japanese white beauty, the residues of which could still be detected in my interviews with the women in Indonesia. This nonetheless explains how in Indonesia, lighter is not always better.

In the early twenty-first century, this complex relationship between skin colour and race became even more complicated. The post-1998 reform era saw an increase in publications of translated Western magazines, including the transnational women’s magazine Cosmopolitan. In these magazines, one would find advertisements, including for skin whitening creams, featuring transnational stars. In other words, if in previous years, one would see a foreign celebrity advertising product from their own country, during the post-reform era, these celebrities no longer advertise products only from their countries.

For instance, Choi Ji Woo, a South Korean actress/celebrity, advertised the France-based ‘DiorSnow Pure White’; Sammi Cheng, a Hong Kong actress/singer, modeled for Japanese SK-II’s ‘Whitening Source Skin Brightener’; Michele Reis, a Hong Kong supermodel, advertised L’Oréal Paris’s ‘White Perfect’ and ‘White Perfect Eye’; Ploy Chermarn, Thai actress, modeled for L’Oréal Paris’s ‘White Perfect Eye’; and Gong Li, a Chinese movie star, posed for L’Oréal Paris’s ‘Revitalift White’. This marked the beginning of the construction of cosmopolitan whiteness.

Beyond race

By cosmopolitan whiteness, I refer to whiteness when represented to embody the feeling and virtual quality of cosmopolitanism: transnational mobility. I propose the notion of cosmopolitan whiteness as a mode for rethinking whiteness beyond racial and ethnic categories and for thinking about race, skin colour/perfect skin and gender as constructed through feelings. To think about whiteness beyond a racial or ethnic category is not to argue that race and racialisation are irrelevant in thinking about whiteness. Rather, I show that whiteness is also constructed as cosmopolitan and that race and racialisation operate in concert with cosmopolitanism in these whitening advertisements. By pointing out a new category of whiteness that is not merely racially or biologically constructed, as described above, I point to the idea that desire for whiteness in Indonesia is not the same as desire for Caucasian whiteness.

Cosmopolitan whiteness is a signifier without a racialised, signified body. It can and has been modelled by women from Japan to South Korea to the United States. There is no one race or ethnic group in particular that can occupy an authentic cosmopolitan white location because there has never been a ‘real’ whiteness to begin with. As visual studies scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff points out, cosmopolitan whiteness is not about claiming a form of real whiteness. Rather, it is about appearing white—these skin whitening creams can only make you appear white but cannot make you become a ‘real’ white. The body can only be virtually white. In some sense, this bears a resemblance to postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha’s notion of colonial mimicry, in which whiteness is read as ‘white but not quite’.

What is interesting about cosmopolitan whiteness is that anyone can be cosmopolitan and white—cosmopolitan white, that is. Whiteness here is not simply coded as embodying specific biological features or originating from a specific place, let alone a ‘race’, but also as involving feelings of cosmopolitanness. Cosmopolitanism is the sense of a globe-trotting lifestyle and the luxury of making claims about multiple (virtual) homes. Hence, whiteness becomes one’s access to experiencing cosmopolitanness (even if at times only virtually), and cosmopolitanness becomes one’s access to experiencing whiteness and its signified privileges. In other words, whiteness is not just about skin colour or race; rather, it is about the privileges and cosmopolitan lifestyles and the luxury that are attached to and signifies it.

This new understanding of cosmopolitan whiteness is important because it is the first step to comprehend what makes white, racial and colour privileges even more elusive and harder to achieve and take down.

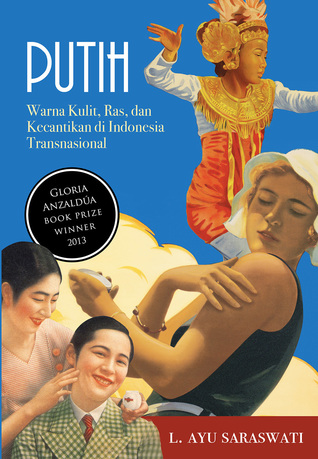

L. Ayu Saraswati is an associate professor of Women’s Studies at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. She is the award-winning author of Seeing Beauty, Sensing Race in Transnational Indonesia (translated as Putih: Warna Kulit, Ras, dan Kecantikan di Indonesia) and a new book, Pain Generation: Social Media, Feminist Activism, and the Neoliberal Selfie. For more information about her work, visit her website, drsaraswati.com.